The Loneliest Place On Earth – Bouvet Island

To take isolation to the extreme, visit Bouvet Island in the southern part of the Atlantic Ocean southwest of the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.

Absolutely no one lives there and it has been dubbed “the most remote island in the world.” Actually, though, they don’t want you to come.

Not much is allowed—no airplanes, no vehicles, no animals that are not native, no boats, and no human disturbance in spaces that are being monitored.

The only way onto the island is by helicopter from a ship, and special permission from the Norwegian Polar Institute must be granted for that.

According to the CIA Library, Bouvet Island is an uninhabited volcanic island near the Antarctic that is not considered a part of that continent but is administered by the Polar Department of the Ministry of Justice and the Oslo Police of Norway who began maintaining it as a nature preserve in 1971.

It is close enough to share the bitter Antarctic cold, is almost completely covered in ice, and is shrouded with fog and clouds the majority of the time.

The island is about 30 square miles with no natural or man-made ports or beaches.

The ice and the sheer cliffs make it nearly impossible to get on the island, and about the only sign of human activity is an automated meteorological station set up in 1977 by Norwegian scientists to track the weather as well as the distribution of fur seals and penguins on the island.

The highest point is Olavtoppen, the peak of the volcano that is the island, which is about two and a half thousand feet above sea level, just north of the island’s center, and is usually filled with ice.

There is a lively wildlife population with Antarctic fur seals, elephant seals, chinstrap and macaroni penguins, and twelve species of birds including several species of petrel, albatross, prion, and gulls.

Bouvet Island or Bouvetøya, as the Norwegians call it, was, according to the Norwegian Polar Institute, discovered in 1739 by Jean-Baptiste Lozier Bouvet, a French navigator and lieutenant of the French East India Company.

Because he didn’t note the proper navigational location, it was forgotten again until 1825 when the British seal hunting captain, George Norris, claimed it for the Crown and named it Liverpool Island.

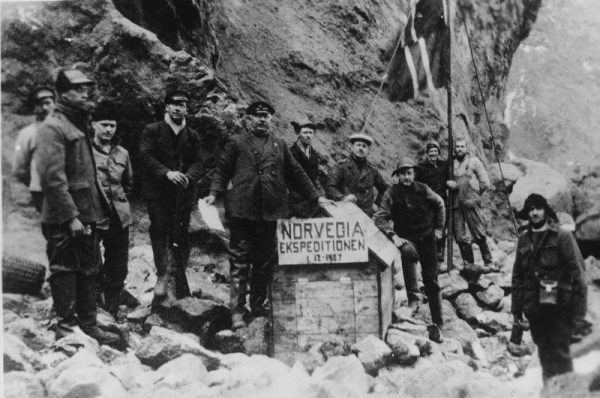

Nothing was done with the island until 1927 when Norwegian shipowner and whaling tycoon, Lars Christensen of Vestfold, organized several expeditions with Harald Hornvelt as captain.

According to Antarctica in International Law at Google books, they erected a small hut which, in their culture, was akin to planting a flag, stirring up the interest of Great Britain.

In 1929, Britain allowed seal hunters and whalers to hunt in the waters off Bouvet Island causing Norway to announce they owned the claim to the island. T

hey claimed Liverpool Island and Bouvet Island were not the same place and, even if they were, Britain hadn’t been doing a good job maintaining their claim.

After ten months of arguing, Great Britain finally conceded as long as Norway recognized certain areas as British due to the right of discovery and agreed not to use those lands.

For the next few years, the Antarctic region was subject to a flurry of countries attempting to make claims to different areas of land.

The British, the United States, Argentina, Chile, Germany, and the U.S.S.R. all began waving declarations about affirming their rights and attempting to establish bases, a dispute that wasn’t settled until the 1970s.

If someone truly wants to visit the island and successfully collects all of the necessary paperwork, they must have their own transportation, ship, and a helicopter.

As far as safety goes, a visitor is on their own; there are no rescue services and there are frequent landslides as well as ocean swells, earthquakes, and the occasional volcanic eruption.

It could take hours or even days for the fog to lift enough to allow a helicopter landing, so a visitor must have accommodations on a ship with no time restrictions.

Crater Five Miles Wide, Made its Way Through 5,000 Miles of Mantle

Even scientists who manage the weather stations are only allowed there between the first of November and the first of May. It is a place of total isolation that makes our current quarantine seem like a party.