Scientists Want to Produce Seaweed That Stops Cows Burping Methane

Driving in the country, one often sees herds of cows. These ubiquitous creatures are usually very mellow and don’t present a danger to anyone – unless they burp. As it turns out, cows release methane into the air when they burp, mostly because of the fact that they chew their cud as do other ruminant animals.

Ruminants, such as deer, sheep, camels, giraffes, and goats, do not actually have four stomachs as is commonly believed. They have compartmental stomachs: one stomach with four compartments.

According to Cattle Empire, when these animals eat, they chew just enough to wet the food and then swallow. After partial digestion, the food comes back up and the animal chews more. It is necessary for complete digestion and the good health of the animals.

EurekAlert! tells us that a dairy cow burps on the average of three hundred eighty pounds of methane a year. Multiply that by an average herd of fifteen to twenty cows on each dairy farm and there is an obvious problem. The burps account for twenty-six percent of the total methane emissions from the United States alone, according to National Geographic.

Scientists have been trying for many years to find a solution to the issue. In 2011, an Iranian team tested sheep with garlic oil, turmeric powder, and an additive called Monensin, a polyether antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces cinnamonensis that alters volatile fatty acid production in the rumen, the first compartment of the stomach, none of which made any marked difference.

International Milk Genomics Consortium reports that in 2015, Dr. Alexander Hristov, Distinguished Professor of Dairy Nutrition from Pennsylvania State University, ran a study feeding a chemical compound, 3-nitrooxypropanol (3NOP) which was identified by a computer model in a laboratory in Basel, Switzerland.

To test the new compound, forty-eight Holstein cows were fed different amounts of 3NOP in their food while their emissions, health, and milk production were closely monitored.

After three months, the cows that were fed the most 3NOP were found to have generated thirty-two percent less methane than the cows that ate the exact same food without 3NOP; although they did produce more hydrogen, which was expected.

Their appetites were not affected, and the cows actually gained weight which was attributed to the food energy normally lost as methane is created. Their protein and lactose levels were increased, and no detrimental effects were observed.

In 2016, a Danish team of scientists began testing the effects of oregano, but no results have yet been published.

Another method of reducing bovine burps has been tested by Breanna Roque, an Animal Biology Graduate Group Student from the University of California, Davis campus.

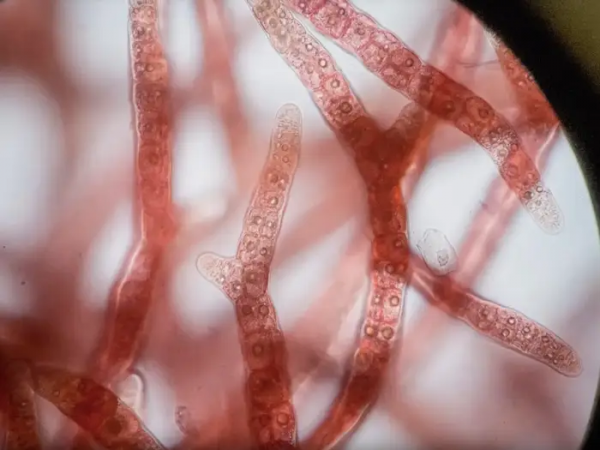

Working under Dr. Ermias Kebreab, Associate Dean for Global Engagement in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and director of the World Food Center, the research team is feeding their cows Asparagopsis taxiformis, a species of red macroalgae that grows in tropical warmth, usually referred to as red seaweed.

One group of cows was fed one percent while another was fed half a percent of seaweed; they showed a sixty-seven and twenty-six percent reduction of methane respectively.

According to Discover, Roque claims the seaweed contains bromoform, a brominated organic solvent, a colorless liquid at room temperature with very high density that inhibits the enzyme that produces methane. They are currently testing the seaweed in beef cattle. Results from long term testing regarding any change of flavor or color in the meat and milk from these cows has yet to be conducted.

While simply adding seaweed to animals’ diets could be a massive breakthrough, other scientists question the viability of the undertaking.

Concerns include the animals’ digestive systems building up an immunity to the effects of the seaweed, the difficulty of production and storage of large quantities of Asparagopsis taxiformis, long term effects on the health of the herds, and the fact that some of the cows don’t seem to like the taste.

Another Article From Us: Thawing Permafrost Could See Anthrax & Prehistoric Diseases Return

While the current studies are showing some positive results, it appears that there is much more research to do on this often ignored contributor to ozone damage.