How much is a National Park worth to you?

Last fall, the National Parks Service proposed a plan to increase entrance fees to 17 of the most popular National parks by more than double. Ryan Zinke, secretary of the interior, proposed raising entrance fees at parks such as Zion, The Grand Canyon, and Joshua Tree from $25 to $70. The increase came as a solution to the Parks Service’s mounting list of unattended projects and increasing budget deficit. In total, unattended projects are tallied at over ten billion dollars.

However, when Zinke proposed this massive fee hike, the backlash was swift and strong. Over the two-month public comment period, the vast majority of public input was strongly negative. Most Americans said that if entrance cost $70, they would likely consider a different destination for family vacation. In the end, the fee hike was reconsidered.

Instead, park fees will be rising by a mere $5 instead of the proposed $45. This won’t affect nearly all of the National Parks. However, even this small increase at the most popular ones is expected to raise around $60 million per year. And although that may seem like a lot of money to keep the parks going, it is still only a fraction of the total budget deficit the organization is facing.

How much is land worth?

So how do you put a price on a National Park? What are our public lands worth to us? It’s been a big debate over the last year. Especially since President Trump made massive slashes to the protected area of Bears Ears National Monument.

In that case, it seemed pretty easy to put a price on public lands. There was oil to be had in what was a protected area. By opening up that land to drilling and industry, Trump made way for a significant amount of revenue production. However, that doesn’t necessarily get at the heart of the question.

After all, just because a land can produce a certain amount of money doesn’t mean that that’s what the land is worth. It’s an age-old question. Does land, wilderness, and natural beauty have intrinsic value? Is the monetary value of a land based on the monetary value it can produce?

When it comes to the National Parks currently in question, it’s not as easy for anyone to answer as it was with Bears Ears. This time, there’s no oil at stake, no revenue stream other than tourism to tap.

How do you put a price on a park?

The big debate here, is how much should American’s have to pay to visit what were originally designated as their own public lands? After all, National Parks as they were conceived are meant to be free places where we could visit in nature’s beauty right? Well… sort of.

Although it is true that the National Parks Service designated the first parks without entrance fees, the founders were not fooled into thinking they would not need revenue to self-sustain. Initially, this was achieved by leasing to businesses and private entities within the parks. Visitors didn’t pay entrance fees. However, starting in the early twentieth century, first at Mt. Rainier and then soon after, at many other National Parks, auto entry fees were introduced. This was done to offset the cost of road building.

Since the very beginning, the mentality of charging entry fees to National Parks was summed up by Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane in 1918 saying “development of the revenues of the parks should not impose a burden upon the visitor”. That phrase came up nearly one hundred years later during a discussion of proposed fee increases.

And although $70 clearly does impose a burden on the visitor, is it reasonable to charge $30? After all, most people driving a car into the park can afford that. Unless you live within a couple of hundred miles of the park, you’ve already spent more than that in gas just to get to the gates. That’s not to mention the incredible burden that mounting tourism puts on the land itself. It takes hard work and wages to maintain public lands and prevent the loss of these natural spaces.

What does a budget deficit mean for parks?

If we don’t find ways to fund the National Parks Service’s budget, then that means that parks fall into disrepair. At first, that means worse roads, poorly maintained facilities, and less trail maintenance. It all seems reasonably harmless. After all, those problems affect the visitors more than the park itself.

However, once you start to examine the deeper implications of an underfunded Park Service, you start to uncover bigger impacts. That’s because these funds don’t just rebuild the human amenities in National Parks. They also deal with massive erosion issues, conservation, reforestation, and habitat protection. This budget deficit doesn’t just mean a less glamorous stay for visitors, but also less impact reduction for the wildlife we are visiting.

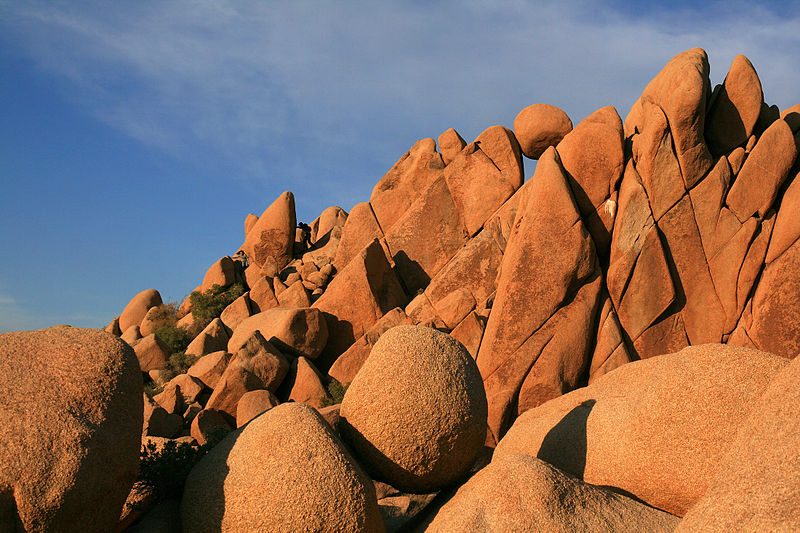

I mean, when it comes down to it, I’m a rock climber. I don’t have a lot of money, yet I spend a vast amount of my time every year in National Parks enjoying these public lands. It’s easy for me to say I’m in support of lower or no fees because I would rather buy climbing gear than park passes. However, it’s not that simple. Sure, perhaps public lands are meant to be free for all of us to enjoy. But when ‘all of us’ becomes hundreds of thousands of visitors to a single park per year, such as Joshua Tree, where do we draw the line?

A park can’t repair itself, it can’t clean itself, and it can’t sustain itself when it sees that kind of traffic. The money for conservation and restoration has to come from somewhere. So where should it come from?

Who should have to pay for National Parks?

That brings us to the next contentious issue in this debate. Who pays for the parks? Is it the visitors who come by the hundreds of thousands every year? Should it be the average taxpayer who may or may not choose to visit? Or should foreign tourists pay extra as they arrive on massive buses and swarm the park? All of these options have been implemented or suggested, and each comes with its own pros and cons.

If visitors take the brunt of the expense, then they wind up paying an awful lot of money to visit. Maybe even somewhere in the ballpark of $70, which, to many is just not acceptable. However, if the federal government winds up paying for most of the cost to keep entrance fees low, that money is actually paid by the average tax payer. Let’s be honest, the majority of people paying taxes aren’t even visiting these parks.

Several people have suggested raising the fee for large tour buses to enter. It’s understandable, these groups swarm over the parks in a manner that’s easy to be annoyed by. If you’re a local trying to enjoy the scenery, it’s not hard to get mad at these groups for clogging up the arteries of our National Parks and overrunning their natural beauty. Some people take it even farther and cite the fact that these groups are usually mostly foreigners, so they should pay extra to use the parks.

At first that may seem a bit discriminatory. However, there are rational voices on both sides of the argument. After all, they are American National Parks, and they are here for us to enjoy. Although we want visitors from around the world to be able to enjoy them too, some argue that it’s reasonable that they have to pay more for entrance to American National Lands. Other’s contend that that’s the exact kind of discrimination that causes us to stand out as less than the friendliest nation. Others even go so far as to call the idea racist. Now, that would only be true if the fees were based on race or ethnicity, so that’s definitely taking it a little too far.

How to get into National Parks for free, or at least less

I’m not trying to say I have the answers to all or even any of these questions. In fact, I don’t know the first thing about government programs, budgeting, or the complex nature of funding on such a monumental scale (…see what I did there?). However, I do know how you can get into the parks for the best rates, or even for free on certain days.

If you’re like me and plan on spending a lot of time in National Parks in the next year, you should buy an annual pass right off the bat. Prices may go up in the near future, but annual passes currently sell for $80 and can be purchased online or at the entrance to any of these National Parks. If you visit just three of these big parks during peak season, you’re already going to be spending more than the cost of the annual pass. So just get it from the start and save money. Plus, maybe that will encourage you to go see more parks!

Or, if you just want to do one or two-day trips this year to see a specific spot, then check out free admission days. The National Parks Service offers free admission to all National Parks on certain days of the year. A couple of holidays as well as the anniversary of the National Parks Service open all the gates free of charge. Of course, the parks are also sure to be packed to the gills on these days, but maybe that’s worth the thirty bucks you’ll save.

Respect and protect our lands

Whatever your position on paying for National Parks, one thing’s for sure. We are all lucky to have such vast natural spaces available to us. Not many countries have protected lands, and even fewer preserve them in the size and way that we do. So most importantly, be thankful for the opportunity to visit these places. Whether you’re going to one of the many free National Parks and monuments, or you have to pay an entry fee, be grateful for the opportunity.

The second thing you need to remember, is that freedom isn’t free, so to speak. Although these lands are protected today, it’s become increasingly clear in the past couple years that when the industry takes an interest, that can change. Just look at Bears Ears National Monument if you need an example. So be sure to stand up for our public lands whenever they are threatened. Say no to corporations and big business that wants to take any part of our protected lands away.

And lastly, get involved. Whether that means making a few visits to National Parks near you, volunteering on a trail crew, or getting involved in your local legislature. The more citizens that make use of these parks and take stewardship seriously, the more resources the parks will have. These places aren’t protecting themselves. They’ve been preserved by dedicated Americans fighting for their protected status over more than a century. If we aren’t watchful and wise, we may see more reductions, restrictions, and removal of public lands to come.

It all brings me back to the very first question I asked. How much are National Parks worth to you?

If you have any comments then please drop us a message on our Outdoor Revival Facebook page

If you have a good story to tell or blog let us know about it on our FB page, we’re also happy for article or review submissions, we’d love to hear from you.

We live in a beautiful world, get out there and enjoy it. Outdoor Revival – Reconnecting us all with the Outdoors.