1911 saw Ishi emerge from the Californian wilderness

At the end of the summer of 1911, a weak, starving native American man emerged from the Butte County wilderness into Oroville and became an instant sensation.

UC anthropologists Alfred Kroeber and T. T. Waterman identified the man as the last member of the Yahi tribe, people native to the Deer Creek region in California.

When they asked his name, he said: “I have none, because there were no people to name me.” In the Yahi culture, is forbidden to speak the name of the death. The UC anthropologists brought him to live on the Parnassus campus, they named him “Ishi” meaning “man” in the Yahi language.

Ishi was 50 years old when he was first introduced to the “civilized world” and lived most of his life outside the modern society.

He was widely proclaimed as the “last wild Indian” in America and journalists followed him everywhere to capture his initial reactions to the world outside the wilderness.

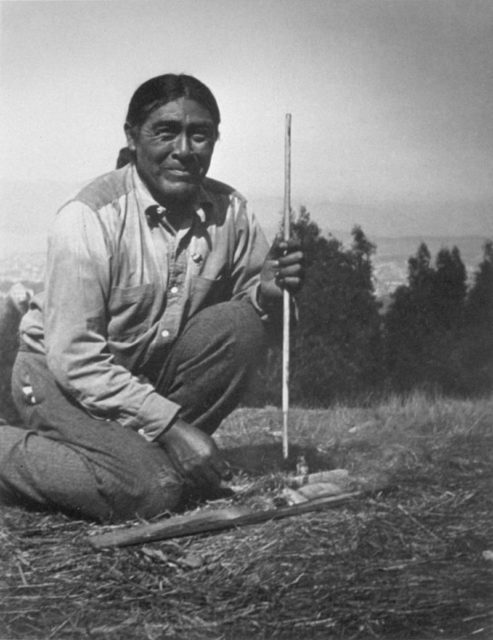

Ishi in 1913

Ishi in 1913

Outside of his natural habitat, Ishi was often in the newspaper headlines, filled with anecdotes referring to his reaction to 20th-century technological wonders like airplanes and streetcars.

Eventually, Ishi adapted to this “new world of wonders” and spent the rest of his life as a research assistant in a university building in San Francisco.

But who was Ishi before he became the last man of his tribe?

In 1800, there were 300,000 Indian people living in the wilderness in California. After the arrival of the white man, by 1900 only 20, 000 remained.

The gold rush meant tens of thousands miners and settlers arrived in Northern California, forcing Indians from their native lands into cities and onto reservations.

The gold mining damaged water supplies; the fish were killed, and the deer fled the area. As well as destroying the natural habitat of the Indians and of the animals, the settlers brought diseases such as smallpox and measles with them.

The Northern Yana group became extinct, and the central groups of the Yahi population dropped dramatically.

In the search for food, they came into conflict with settlers.

Ishi and his family were attacked at the Three Knolls Massacre in 1865, in which 40 of their tribesmen were killed. The massacre began while the Yahi slept in bed. Around 33 Yahi, among which was Ishi, survived.

Ishi and his family went into hiding for the next 44 years, while their tribe was slowly going extinct.

Before the California Gold Rush, the Yahi population estimated 404 in California.

In 1908, a group of surveyors stumbled upon a camp with two men, a middle-aged woman, and an elderly woman. Those people were Ishi, his uncle, his younger sister and his mother. Ishi, his sister and uncle, fled while his mother hid herself under a blanket as she was very sick and unable to flee. Ishi’s mother died soon after he returned to the camp, and his sister and uncle never came back.

Ishi now completely alone, spent the next four years starving and wandering around in the wilderness. With nowhere to go and slowly starving to death, on August 29 in 1911 Ishi walked out from his world and emerged into the western world.

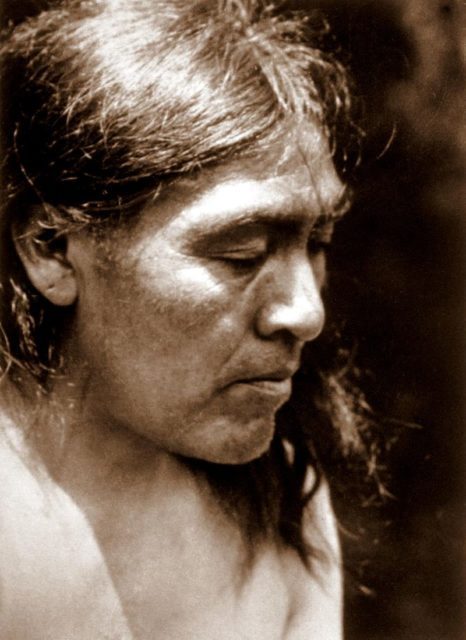

Ishi

Ishi

After the townspeople had noticed him, the local sheriff took the man into custody for his own protection.

The “wild” man without name stirred the imagination and attention of thousands of onlookers and curiosity seekers. The University of California brought him to the University. Ishi was then housed on campus in an old law school building.

While being studied at the University, Ishi also worked as a research assistant and lived in an apartment for most of the remaining five years of his life.

The director of the museum Alfred L. Kroeber, studied Ishi at length over the years to reconstruct Yahi Culture. Ishi provided valuable information that helped the project, such as describing family units, naming patterns, the ceremonies, and everything that he knew about his culture.

Ishi’s quiver of arrows.

Ishi’s quiver of arrows.

Ishi didn’t last long in the modern world. Being from the wilderness, Ishi had no immunity to the ‘diseases of civilization’ and was often sick. The Professor of Medicine at UCSF, Saxton T. Pope regularly supervised Ishi’s health and the two became close friends.

Ishi taught the doctor how to make bows and arrows in the Yahi way and they often hunted together,

On March 25, Ishi died of tuberculosis.

If you have any comments then please drop us a message on our Outdoor Revival facebook page

If you have a good story to tell or blog let us know about it on our FB page, we’re also happy for article or review submissions, we’d love to hear from you.

We live in a beautiful world, get out there and enjoy it.

Outdoor Revival – Reconnecting us all with the Outdoors.